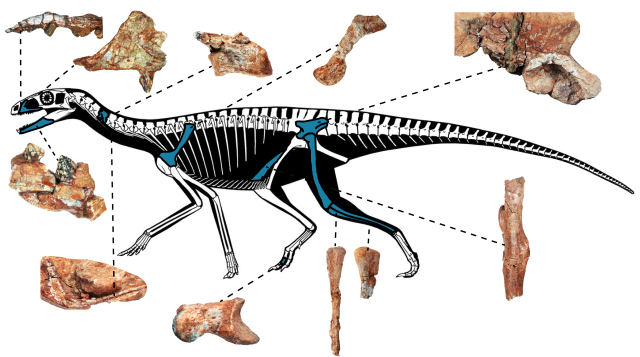

In blue, some of the bones from the new silesaurid analyzed by researchers on the Ribeirão Preto campus of the University of São Paulo (USP) (image: Gabriel Mestriner)

The fossil assemblage was found in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, one of Brazil’s richest paleontological regions. The bones belonged to animals that lived between 247 million and 208 million years ago. It is difficult to confirm they can be considered species of dinosaur.

The fossil assemblage was found in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, one of Brazil’s richest paleontological regions. The bones belonged to animals that lived between 247 million and 208 million years ago. It is difficult to confirm they can be considered species of dinosaur.

In blue, some of the bones from the new silesaurid analyzed by researchers on the Ribeirão Preto campus of the University of São Paulo (USP) (image: Gabriel Mestriner)

By André Julião | Agência FAPESP – A set of fossils recovered in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil’s southernmost state, has brought an extra layer of complexity to the study of the evolutionary history of silesaurids, a family of dinosauriforms (dinosaurs and their close relatives) that lived in the Triassic period between 247 million and 208 million years ago.

In an article published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, researchers affiliated with institutions in Brazil and the United States show that even with the new fossil assemblage it is difficult to confirm that these animals were part of the evolutionary history of the dinosaurs.

The fossil assemblage was found in 2014 at a site called Waldsanga in the Santa Maria Formation, one of the most fossil-rich rock bodies in Brazil. The bones belonged to more than one individual, and it is impossible to be sure they all belonged to the same species, although the evidence suggests they did. Above all, it is an important record of animals that lived in the area during the Triassic.

The assemblage is the fourth find relating to silesaurids in Brazil and the second from the Carnian age (237-227 mya). It is labeled UFSM 11579 and is deposited at the Stratigraphy and Paleobiology Laboratory of the Federal University of Santa Maria (UFSM).

“When we inserted the assemblage’s characteristics into various phylogenies [evolutionary histories] of the group, we didn’t specify whether the silesaurids were dinosaurs or close relatives of dinosaurs. In any event, the anatomical and phylogenetic evidence validated the find as belonging to the silesaurid lineage, albeit not named as a new species,” said Gabriel Mestriner, first author of the article. The study was part of his PhD research at the University of São Paulo’s Ribeirão Preto School of Philosophy, Sciences and Letters (FFCLRP-USP) with a scholarship from FAPESP.

“Because the bones are disarticulated [separated, not joined up], and considering the uncertainty about the group’s evolution, we concluded that adding another species in this case wouldn’t be a solution but would make the problem worse,” Mestriner said.

The silesaurids were mostly quadrupeds and 1m to 3m in length. They had long hind legs, and their front legs were slender. Remains have been found in present-day South America, North America, Africa and Europe.

The first species, described in 2003, was Silesaurus opolensis. Its remains were found near Opole in Silesia, Poland – hence the name. “It’s the species with the most complete skeleton to date. In addition, the find comprised several hundred well-preserved bones relating to several individuals. About ten more species have been described since then, but their remains were more fragmented,” said Júlio Marsola, second author of the article. Part of his postdoctoral research at FFCLRP-USP was supported by a scholarship from FAPESP. He is currently a professor at the Dois Vizinhos campus of the Federal Technological University of Paraná (UTFPR), also in the South of Brazil.

The study was part of the Thematic Project “Dinosaur diversity and associated faunas in the Cretaceous of South America”, funded by FAPESP and led by Max Langer, a professor at FFCLRP-USP and last author of the article.

“Although many species have been described on the basis of few bones, the main problem with this group isn’t lack of material, but ambiguous anatomy: parts of the skeleton are similar to the dinosaurs, others less so. It’s difficult to resolve their phylogenetic relationships,” Langer said.

Different teeth

In another study, published in 2021, the researchers focused on dental anatomy to look for fresh evidence of the silesaurids’ place in the dinosaur family tree. Their analysis of tooth attachment and implantation in four species, including UFSM 11579, concluded that these species’ teeth were mostly fused to the jawbone, lacking the periodontal ligament (soft connective tissue between teeth and bone) present in dinosaurs and extant crocodiles.

“At the same time, however, some of the teeth we analyzed were anatomically closer to those of dinosaurs and crocodiles, as if the silesaurids were evolving in that direction. If so, they could represent an intermediate stage between the ancestral condition [fused teeth] and the derived condition [teeth anchored to alveolar bone sockets by ligaments],” said Mestriner, who conducted the study as part of his master’s research at FFCLRP-USP, with internships at Virginia Tech in the US and the University of Alberta in Canada.

The new dental configuration, which is also seen in humans and other mammals, is considered an important evolutionary advantage for ancestral non-mammals, since periodontal ligaments act as shock absorbers that help reduce the mechanical impact of biting and chewing.

The findings on dental implantation are not sufficient to differentiate silesaurids from other dinosauriforms, but make it more likely that they are very closely related to dinosaurs. For Langer, who was principal investigator for both studies, understanding the groups’ evolutionary history is more important than continuing to name new species and can be achieved using the existing data, such as fossils deposited in museums.

“We need more detailed phylogenetic studies by researchers who scrutinize collections to analyze all fossils in a group in pursuit of characteristics that point to kinship within the group or with other groups. The databases we have now are the result of this kind of research, of which there hasn’t been enough. It’s hard work, but we won’t move forward without it,” he said.

The article “Anatomy and phylogenetic affinities of a new silesaurid assemblage from the Carnian beds of south Brazil” is at: www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02724634.2023.2232426.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.