A cave near Varghis Gorge in the Eastern Carpathians, Romania. The Romanian-Brazilian mission will survey and excavate this and other sites where Homo sapiens and H. neanderthalensis may have interacted (photo: Marius Pascu/Wikimedia Commons)

The mission, which will be led by archeologist and anthropologist Walter Neves, aims to understand how the Neanderthals interacted with Homo sapiens, and why they disappeared.

The mission, which will be led by archeologist and anthropologist Walter Neves, aims to understand how the Neanderthals interacted with Homo sapiens, and why they disappeared.

A cave near Varghis Gorge in the Eastern Carpathians, Romania. The Romanian-Brazilian mission will survey and excavate this and other sites where Homo sapiens and H. neanderthalensis may have interacted (photo: Marius Pascu/Wikimedia Commons)

By José Tadeu Arantes | Agência FAPESP – Scientists do not yet know why the Neanderthals disappeared – whether they were wiped out by Homo sapiens in violent conflict, competition for natural resources, diseases transmitted by our ancestors, or a combination of all three. Alternatively, they may have become extinct for an entirely different reason.

Whatever the reason, two things are certain. First, the disappearance of H. neanderthalensis “coincided” with the arrival of H. sapiens in Europe, after modern humans left Africa to live for many generations in the Middle East. Second, there was sexual contact between the two species, as evidenced by the Neanderthal genes in the DNA of modern humans.

Neanderthal DNA accounts for only a very small percentage of our genome (2%-4%), but is found in all human populations alive today. Two skulls of H. sapiens dating from 35,000-40,000 years ago and excavated in Romania contain a larger proportion (6%). Typically Neanderthal artifacts have been found in the area, but no bones, which should be there, as the Balkans connect the Middle East, Africa and Asia with Western Europe, and Neanderthals almost certainly lived there, given the larger percentage of their DNA in these skulls.

Veteran researcher Walter Neves traveled to Romania to scan archeological and paleontological sites in search of skeletal remains that could prove the link. “The first step is to work out which are the most likely sites. The next will involve digs at sites with remains dating from more than 40,000 years ago in hopes of finding Neanderthal remains,” Neves says.

The study will be conducted by a Romanian-Brazilian scientific mission and supported by FAPESP via the project “The interaction between Neanderthals and modern humans in the Balkans: a paleoanthropological approach”.

“Three H. sapiens skulls discovered in Romania have Neanderthal-like features, suggesting that interbreeding may have occurred there. More recently, Neanderthal DNA has been found to account for 6% of the DNA from two of these three skulls. This is considered a high proportion. The two species clearly swapped genes in that region,” Neves says.

Previous finds in the Romanian Carpathians show this was a route into Europe for the first groups of H. sapiens. Neves wants to identify the exact locations where they met Neanderthals and see if he can discover what happened next.

“We’ll look for sites in the Varghis Gorge, north of the Perani Mountains in the Eastern Carpathians. This is highly likely to be where they met. Digs in the region’s caves at the level corresponding to the Middle Paleolithic could produce crucial information about how the two species interacted and also about how they coped with the climate change that occurred in the region,” he says.

The researchers will conduct archaeological surveys using computerized documentation and management methodologies they have developed. They will deploy various methods to determine the chronology of anthropogenic deposits, including radiocarbon, uranium-thorium dating and optically stimulated luminescence; investigate micromorphology and sediments to understand the formation of the archaeological sites; and analyze fossil remains morphologically and taxonomically, including molecular examination, to determine diet, mobility and population history.

Common ancestor

H. sapiens and H. neanderthalensis are descendants of a common ancestor, H. heidelbergensis, which is thought to have evolved from an African form of H. erectus some 600,000 years ago. They probably split off from H. heidelbergensis as a result of migration to different habitats. H. sapiens emerged in Africa some 230,000 years ago and remained there for a long period, followed by migration to the Middle East, Near East, and eventually Europe. The Neanderthals are believed to have emerged in Europe, where they lived between 250,000 and 40,000 years ago, disappearing at about the same time as H. sapiens arrived there.

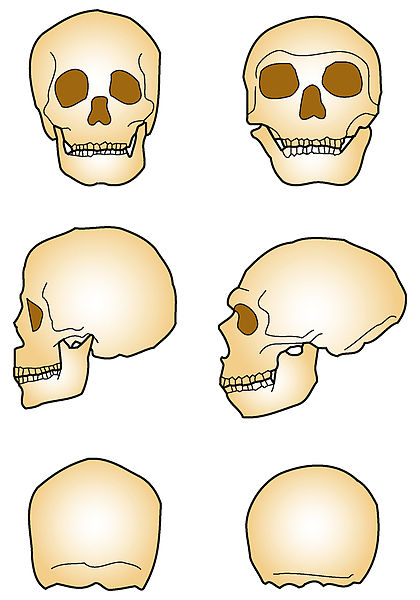

“H. neanderthalensis had an elongated neurocranium, a flattened forehead and a protruding face. His brain was about 1,550 cubic cm in volume – larger than ours, which is 1,350 on average – but his prefrontal cortex was less developed. Hence the receding forehead,” Neves says. It may be possible to find out from the digs in Romania how these first human inhabitants of Europe lived, how they interacted with H. sapiens migrants from the east, and whether this interaction determined their disappearance.

Comparison between the skulls of Homo sapiens (left) and Homo neanderthalensis (image: Wikimedia Commons)

The mission is important geopolitically, too. “Brazil counts for nothing in the field of paleoanthropology,” Neves says. “The only Brazilian research group that studies human macroevolution is ours, at the University of São Paulo’s Institute of Advanced Studies [IEA-USP]. What usually happens is that researchers from developed countries go looking for the ancestors of modern humans in Third World countries. This gives them what we jokingly call ‘fossil power’, which is very important in my field. We’re now doing the opposite. We’re Third World researchers going to study human macroevolution in the First World. This is important for Brazil because of all the publicity given to research on human evolution.”

It will be the second paleoanthropological mission undertaken abroad by Brazilian researchers. The first was to Jordan and was also led by Neves. It was funded mainly by FAPESP. “In Jordan, we excavated remains of our ancestors dating from 2.5 million years ago. This time, we’ll be working on remains from between 60,000 and 40,000 years ago. Our dream for the future is a Brazilian mission to Africa,” he says.

In Jordan, Neves and collaborators found the oldest lithic artifacts encountered outside Africa. “The discovery enabled us to show that the first ancestors of current human populations outside Africa to leave that continent did so 700,000 years earlier than was previously thought, completing changing the view on dispersal of the first representatives of the genus Homo,” he recalls, adding that the mission to Romania may well produce equally significant findings.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.