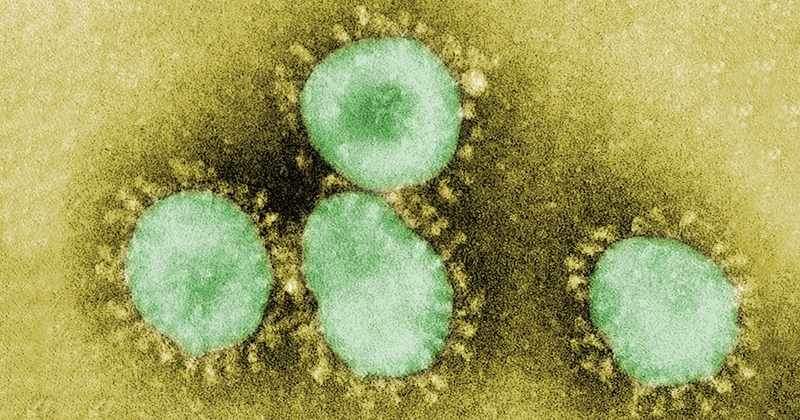

Study led by researchers at Oxford University suggests that after successive infections by the coronaviruses that cause common colds throughout life the defense system becomes specialized and cannot recognize emergent varieties such as SARS-CoV-2 (image: Wikimedia Commons)

Study led by researchers at Oxford University suggests that after successive infections by the coronaviruses that cause common colds throughout life the defense system becomes specialized and cannot recognize emergent varieties such as SARS-CoV-2.

Study led by researchers at Oxford University suggests that after successive infections by the coronaviruses that cause common colds throughout life the defense system becomes specialized and cannot recognize emergent varieties such as SARS-CoV-2.

Study led by researchers at Oxford University suggests that after successive infections by the coronaviruses that cause common colds throughout life the defense system becomes specialized and cannot recognize emergent varieties such as SARS-CoV-2 (image: Wikimedia Commons)

By André Julião | Agência FAPESP – An international research group led by scientists at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom have developed a mathematical model that may explain why children are less susceptible to COVID-19 while older people frequently become critically ill when infected by the novel coronavirus.

The researchers correlated the age of infected subjects with the severity of symptoms in cases documented in Europe, concluding that exposure in childhood to other endemic human coronaviruses (eHCoVs), which mostly cause only common colds or similarly mild respiratory symptoms, triggers an immune response that may also protect the organism against the novel coronavirus. After successive exposures to eHCoVs during adulthood, however, the immune system becomes too specialized to recognize and combat emergent viruses such as SARS-CoV-2.

The study was supported by FAPESP. A report on its findings is published on medRxiv, a preprint platform for new medical research that has not yet been peer-reviewed. Besides the authors from Oxford University, the paper is signed by researchers affiliated with Tel Aviv University in Israel, and three Brazilian institutions: Oswaldo Cruz Institute, the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), and the University of São Paulo (USP).

“We can now see clearly that most children and adolescents experience mild or no symptoms of COVID-19 whereas older people risk developing more severe cases of the disease. Our hypothesis was that this difference in severity had something to do with different degrees of exposure to endemic coronaviruses, which are estimated to be responsible for almost a third of common colds,” Francesco Pinotti, a researcher at Oxford University and first author of the article, told Agência FAPESP.

Seven coronaviruses are known to infect humans. SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, appeared late last year, whereas the other two that can cause severe respiratory problems, SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV, first appeared in 2002 and 2012 respectively.

The group set out with the assumption that childhood exposure to endemic human coronaviruses (HCoV-229E, -NL63, -OC43, and -HKU1) can induce cross-protection – immunity not just to these viruses but also to novel varieties like SARS-CoV-2, Pinotti explained.

Older people have been exposed to eHCoVs throughout their lives, and their immune system has become specialized in combating them. This specialization, or homotypic immune response, protects them against infection by eHVoCs, but with the drawback that they have lost cross-protection, or heterotypic immunity, against SARS-CoV-2.

The first eHCoV infection typically occurs before a child is five and the most severe cases of COVID-19 among children and adolescents also occur in this age group. Nevertheless, they are far less severe than among adults generally, and especially among the elderly. The model shows that protection peaks around the age of five and steadily declines thereafter.

Cross-protection

“The study discusses a possible explanation for this age-related severity profile of the disease. It also draws attention to the need for more research on cross-reactivity between endemic coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2. The role of exposure to eHCoVs, which are very common everywhere including Brazil, has been underestimated during the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Daniel Santa Cruz Damineli, a researcher in USP’s Medical School (FM) and a co-author of the study, supported by a postdoctoral scholarship from FAPESP.

Recently, however, new studies have begun calling attention to cross-protection. A paper published in Science in early August by researchers in the US and Australia reported finding CD4+ T defense cells compatible with an immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and eHCoVs in blood samples taken before the COVID-19 pandemic. About 20%-50% of humans are believed to have these cells, according to some studies.

Damineli belongs to a research group, with members in FM-USP’s Pediatrics Department and the same university’s Institute of Mathematics and Statistics (IME), that is investigating genomic responses in children and adults with asymptomatic and severe COVID-19.

The study is led by Carlos Alberto Moreira Filho, a professor at FM-USP, and is part of a project funded by FAPESP to look for differences in gene expression in these patients’ blood that may explain why some have no symptoms and others become critically ill.

“Immunological studies will be key to elucidating the role of pre-existing immunity during COVID-19,” Pinotti said.

The researchers have not ruled out the possibility that immune system senescence is involved. The idea that overall immunity declines as people age has been used before to explain why older people are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2, but the new model is more precise because it considers immune response variability within age groups, each of which includes people who respond to the virus more or less effectively. The senescence model, on the other hand, simply predicts a gradual deterioration over time and does not consider factors such as differing degrees of exposure to viruses among different individuals.

The study is mainly theoretical and its conclusions hypothetical, Pinotti noted. “Ultimately, data on exposure to HCoVs over time will be needed to test our hypothesis. This is particularly hard to obtain,” he said. However, the study paves the way to more detailed research on the role of cross-protection in immunity to the novel coronavirus and shows the importance of studying the occurrence of HCoVs.

The article “Potential impact of individual exposure histories to endemic human coronaviruses on age-dependence in severity of COVID-19” can be read at: www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.23.20154369v1.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.