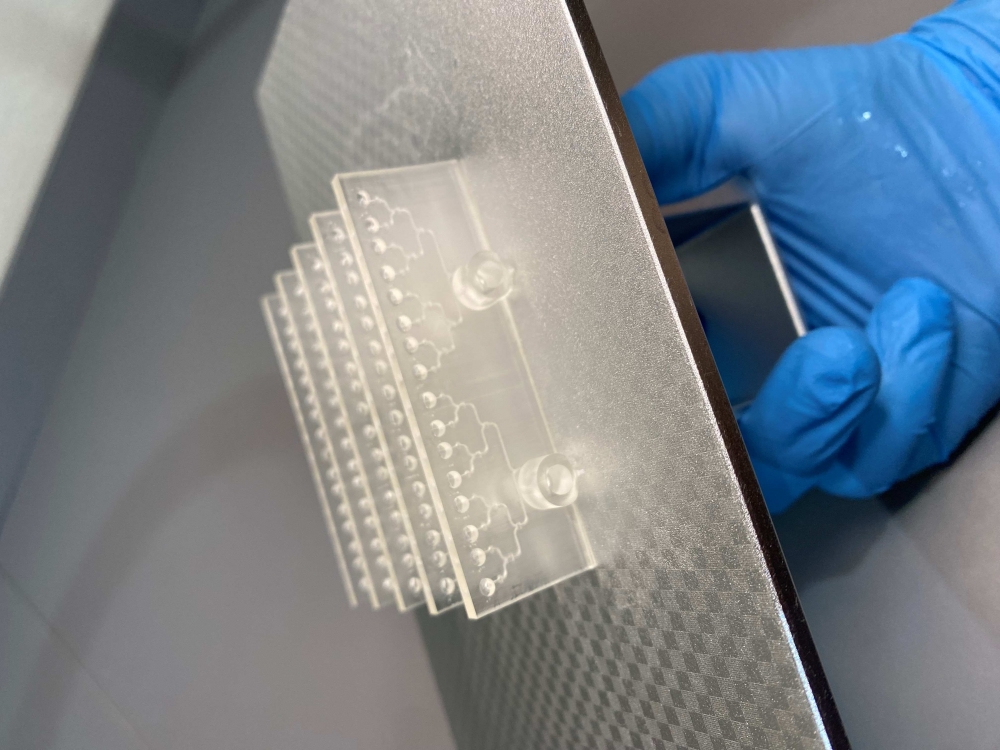

The firm is one of the first to produce microfluidic chips for quick tests using onboard loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) (photo: Doroth)

A technological solution developed by a Brazilian startup with FAPESP’s support detects microorganisms that cause disease in eucalyptus, soybeans and other agricultural plants. They can be detected in grains, leaves and the air.

A technological solution developed by a Brazilian startup with FAPESP’s support detects microorganisms that cause disease in eucalyptus, soybeans and other agricultural plants. They can be detected in grains, leaves and the air.

The firm is one of the first to produce microfluidic chips for quick tests using onboard loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) (photo: Doroth)

By Roseli Andrion | FAPESP Innovative R&D – All living beings have cells containing deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) that carries genetic information for their development and functioning. In agriculture, DNA can be analyzed in search of biological targets to improve processes and to protect crops and animals from attack by microorganisms. This is what Doroth does.

A biotech startup based in Piracicaba, a city in São Paulo state, Doroth is one of the first companies to produce microfluidic chips for quick tests using onboard loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). The lab-on-a-chip technology analyzes DNA to detect mutations, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), transgenes, resistant genes and barcodes (short sequences of base pairs). No laboratories or trained technicians are required, and biological targets for crop treatment are identified directly on-site.

LAMP is a high-performance method used to detect a variety of pathogens, including parasites, fungi, bacteria and viruses. It entails a similar gene amplification technique to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, which was widely deployed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“A PCR test for COVID-19 can now be more than 99% accurate, reaching 99.6% with the right protocol, but it has to be processed in a laboratory. Our solution takes this level of accuracy out into the field to help farmers,” said Rodrigo Gurdos, a biotech engineer who founded Doroth and is currently its new business director.

The startup has pioneered this type of monitoring in agriculture and is now focusing on detecting biological targets in grains, leaves and the air, although the method can be applied to any kind of biological sample.

It is supported by FAPESP’s Innovative Research in Small Business Program (PIPE).

Its clients include Suzano, FMC Agrícola, Corteva and Genesis Group. “Corteva wants to detect transgenes in leaves in order to charge royalties. Suzano aims to detect Ralstonia, the bacterium that causes the main eucalyptus seedling disease [bacterial wilt], before the first symptoms appear,” Gurdos said.

FMC Agrícola wants to detect Phakopsora pachyrhizi, a fungus that attacks soybean plants. “This microorganism disperses aerially, and the company wants to detect it before it contaminates crops,” he explained. In particular, the company aims to avoid the onset of Asian soybean rust, the disease that most affects this crop in Brazil and can wipe out an entire plantation without proper management.

The lab-on-a-chip Doroth uses to conduct these tests has all the reagents required to extract DNA from samples and perform a LAMP analysis. “The chip with the sample is inserted into our device, which resembles a capsule espresso machine. You pop in the sample with the chip, and the machine does all the processing automatically without any human intervention,” Gurdos said, adding that the device is built to withstand the harsh conditions typically encountered in the field, including bumpy transportation and high temperatures, among others.

Combating Asian soybean rust

The research that led to the firm’s foundation started in 2018. “At that time we wanted to find out which was the biggest crop in Brazil and the worst disease faced by farmers. The biggest crop was soybeans, with about 43 million hectares, and the worst disease was Asian soybean rust,” he recalled. Farmers tend to try to ward off the disease by spraying crops with fungicide once a fortnight. The soybean cycle lasts about 110 days from planting to harvest. “Spraying occurs four or five times in this period, representing exorbitant and unnecessary costs. We wondered whether this behavior would change if they knew the disease had arrived.”

It was no easy task to develop the solution based on this insight. The technology was very new. They had explored LAMP in 2018, but it became widely used only in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. “The advantage of LAMP is that it requires a single temperature. The reaction is produced in the range of 67 °C. PCR requires thermocycling [cyclical temperature changes], which is very hard to perform outside the laboratory. LAMP testing is quick and highly accurate on site,” Gurdos said. A PCR machine costs as much as BRL 100,000 (now about USD 20,400). “Our product costs a fraction of that amount.”

As time passed, the team discovered other applications for the technology. “An example is identification of resistant genes. Weeds are usually combated with herbicide, but farmers often don’t know which is the best herbicide to use. Our system can determine within one hour whether the species that’s attacking a crop has a gene that’s resistant to a given molecule. The farmer can avoid that active ingredient and choose a more effective herbicide,” he explained.

The startup currently has a staff of 16, most of whom have PhDs, an unusually high proportion in this market, as professionals with doctorates and postdoc qualifications are found mostly in universities. “We have this structure thanks to FAPESP’s support via PIPE. It’s an investment that allows us to make mistakes. Faliure is part for the course in science, but run-of-the-mill investors don’t understand that,” Gurdos said.

The firm is observing other markets, such as cattle breeding and the diseases that disturb this activity. “We can identify the best antibiotic to give cattle for treatment and to stop the disease spreading. We’re not only pioneers but also the only firm that can now perform these tests. We’re in the vanguard of this technology, and we’re very proud of being an entirely Brazilian project,” he said.

Scaling up

The firm aims to industrialize the solution and scale up to mass production within the next two years. “We have to learn how to do this because no such industrial facility exists yet,” Gurdos said. Next, it plans to expand into other segments, such as cattle breeding. “It’s interesting because the companies themselves come to us with their difficulties. We aim to have 30 or 40 professionals in the team by the end of 2025.”

And it does not stop there. Doroth’s technology can be used in extreme situations, such as future pandemics. “Our current focus is agriculture, but there’s nothing to prevent our entirely indigenous technology from being used in other areas in an emergency. That isn’t our focus, but the potential is there if needed,” he said.

Doroth perfected the concept developed by Lucira, the first company in the world to use LAMP for quick COVID-19 testing. “Lucira is our benchmark, but it’s a disposable test kit, whereas in our case only the ‘coffee pod’ is disposable,” he said.

The name Doroth is a Brazilian version of Dorothy, the heroine of the Wizard of Oz and the device used in Twister, the 1996 movie, to release hundreds of sensors into the center of a tornado and send data back to weather scientists on the ground. When the startup was founded, it was called 2-seq, but it soon became evident that this was not a good name. “Twister gave us our first notion of how the Internet of Things [IoT] could be used in agriculture. We liked Dorothy so much that we opted for this name, and everyone likes it,” Gurdos said.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.