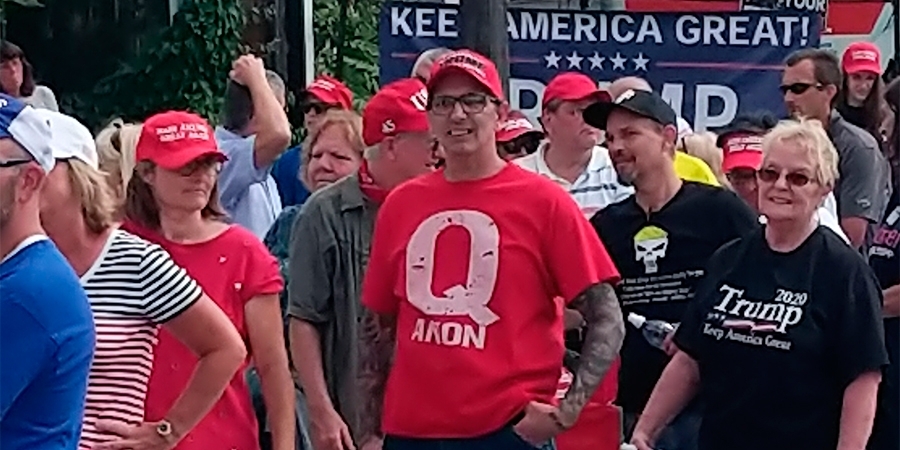

Pro-Vaccine Union, an initiative of the University of São Paulo in partnership with other organizations including Research, Innovation and Dissemination Centers funded by FAPESP, is monitoring anti-vaccine groups on Facebook in an effort to understand the workings of the social media ecosystem that spreads disinformation (photo: Marc Nozell / Wikimedia Commons)

Pro-Vaccine Union, an initiative of the University of São Paulo in partnership with other organizations including Research, Innovation and Dissemination Centers funded by FAPESP, is monitoring anti-vaccine groups on Facebook in an effort to understand the workings of the social media ecosystem that spreads disinformation.

Pro-Vaccine Union, an initiative of the University of São Paulo in partnership with other organizations including Research, Innovation and Dissemination Centers funded by FAPESP, is monitoring anti-vaccine groups on Facebook in an effort to understand the workings of the social media ecosystem that spreads disinformation.

Pro-Vaccine Union, an initiative of the University of São Paulo in partnership with other organizations including Research, Innovation and Dissemination Centers funded by FAPESP, is monitoring anti-vaccine groups on Facebook in an effort to understand the workings of the social media ecosystem that spreads disinformation (photo: Marc Nozell / Wikimedia Commons)

By Maria Fernanda Ziegler | Agência FAPESP – As most countries are preparing or starting to vaccinate their populations against COVID-19, which has so far killed some 2 million people worldwide, anti-vaccine movements fueled by misinformation and conspiracy theories are on the rise, in Brazil and elsewhere.

Experts have stressed that it is not enough to stockpile vaccines, needles, syringes, freezers and other inputs, have enough properly trained personnel to give the jabs, and set up a well-run distribution and logistics network. It is equally important to get public opinion behind the effort to vaccinate at least 60% of the population, and this requires strong pro-vaccine communication.

“We’re seeing an asymmetrical battle. Anti-vaxxer groups in Brazil have grown considerably during the pandemic. They tend to take fake news produced previously and adapt it to the COVID-19 era. It’s much cheaper and easier to churn out fake news and conspiratorial thinking than to conduct a scientific study,” João Henrique Rafael, a communication analyst at the University of São Paulo’s Institute of Advanced Studies (IEA-USP), told Agência FAPESP.

Rafael is one of the prime movers behind the Pro-Vaccine Union (União Pró-Vacina), a group of Brazilians who are monitoring anti-vaccine movements on Facebook. Its website says it aims to bring together academic and research institutions, government and civil society organizations to combat misinformation about vaccines, and to plan and organize joint activities.

Based at IEA-USP Ribeirão Preto (São Paulo State), it partners with the Center for Cell-Based Therapy (CTC) and the Center for Research on Inflammatory Diseases (CRID) – two of the Research, Innovation and Dissemination Centers (RIDCs) funded by FAPESP – as well as Ilha do Conhecimento, Vidya Academics, FEA-RP Gaming Club, Instituto Questão de Ciência and Pretty Much Science.

“Vaccination coverage has trended down for some years in Brazil,” Rafael said. “The last good year was 2015. There are many drivers of anti-vaxxer movements, but the evidence suggests disinformation, lack of communication and insufficient education about the importance of vaccination were responsible for much of the downtrend.”

The Union began researching in November 2019, when no one imagined 2020 would be a pandemic year. The group first set out to discover who was producing anti-vaccine content, where it was circulating, and what the main myths were. They then began producing evidence-based material on the importance of vaccination to individuals and society. They also took steps to try to prevent the spread of misinformation.

“We began organizing our analysis of anti-vaxxers in November [2019], and we had everything ready when the pandemic hit, making it much easier to monitor them and see how they added followers and how they behaved generally,” Rafael said.

But the pandemic has also made it much easier for anti-vaccine groups to grow, not least because they are also about communication. “These groups have been organizing and growing for years. They already had a captive audience. The social media have been a powerful tool for distributing disinformation. It’s hard to fight back,” he said.

The growth has happened not just in Brazil but also in the United States, where anti-vaccine sites have millions of followers. The movement is smaller in Brazil, which has a long history of successful vaccination campaigns. “Even so, the anti-vaccine movement has grown 18% here during the pandemic, with more than 23,000 followers on Facebook alone,” Rafael said.

Empty spaces

Another important point stressed by Rafael is the vacuum left by the large digital platforms. “Measures such as banning, demonetizing or removing content deemed untruthful were taken too late and out of proportion to the volume of disinformation,” he said. “In addition, key institutions that post content relating to vaccination failed to deal efficiently with digital platforms.”

One of the examples investigated is the Facebook page on vaccines maintained by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.

“Communication by this ministry and other bodies wasn’t sufficient to demystify false content and create public trust in the importance of vaccination,” Rafael said. “The ministry’s Facebook page on vaccination, with more than 1 million followers, became static. Early on in the pandemic the channel, which was already important on Facebook, remained non-updated for three months.”

The main trend in false anti-vaccine content identified during the period analyzed was what he calls ideological, involving content posted by people who really believe in anti-vaccine theories and see themselves as on a mission to spread them. Another is commercial, as exemplified by YouTube channels that are not exclusively anti-vaccine but misinform and sporadically offer videos with false content on vaccines to attract viewers and income.

“A third trend, which has emerged more recently in Brazil, is one of the most worrisome because it’s political and fueled by polarization revolving around the pandemic,” Rafael said.

The analysis conducted by the Pro-Vaccine Union at USP also confirmed that content relating to the QAnon conspiracy theory is expanding and merging with content posted by anti-vaccine groups.

QAnon, which started in 2017 on far-right chat forums, is a disproven conspiracy theory alleging that a cabal of Satan-worshipping cannibalistic pedophiles is waging a secret global war in government, business and the media. The FBI has designated QAnon a “domestic terrorist threat”. In August 2020, Facebook took down or restricted thousands of US groups, pages and Instagram accounts associated with QAnon. It took similar action in Brazil in September, removing groups and pages with more than 570,000 followers.

“These actions came too late to prevent the rapid spread of such conspiracy theories by radical political and anti-vaxxer groups,” Rafael said. “QAnon adds more radical layers to the usual conspiracy theories. For example, besides posting fake news on the pandemic, it urges followers to invade hospitals, record videos showing they’re empty and challenge doctors, among other alarming attitudes.”

Two anti-vaccine groups monitored by the Union were not taken down by Facebook and have more than 23,000 followers, acting as a fake news and misinformation hub. “Unlike flat earthers and anti-vaxxers, QAnon incorporates and blends with other conspiracy theories, constantly spreading more extreme novel ideas,” Rafael said. “It’s increasingly radical, fueling people’s despair and fear, which can lead to hate.”

Brazil may see similar trends to the US in the years ahead, Rafael believes. “There’s a risk that this won’t be controlled now and the movement will grow until the 2022 presidential election, when it will be very strong. That’s what happened in the US, where people who bought into QAnon won seats in Congress in the 2020 elections. The time to prevent this and take action to stop the movement from spreading is now,” he said.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.