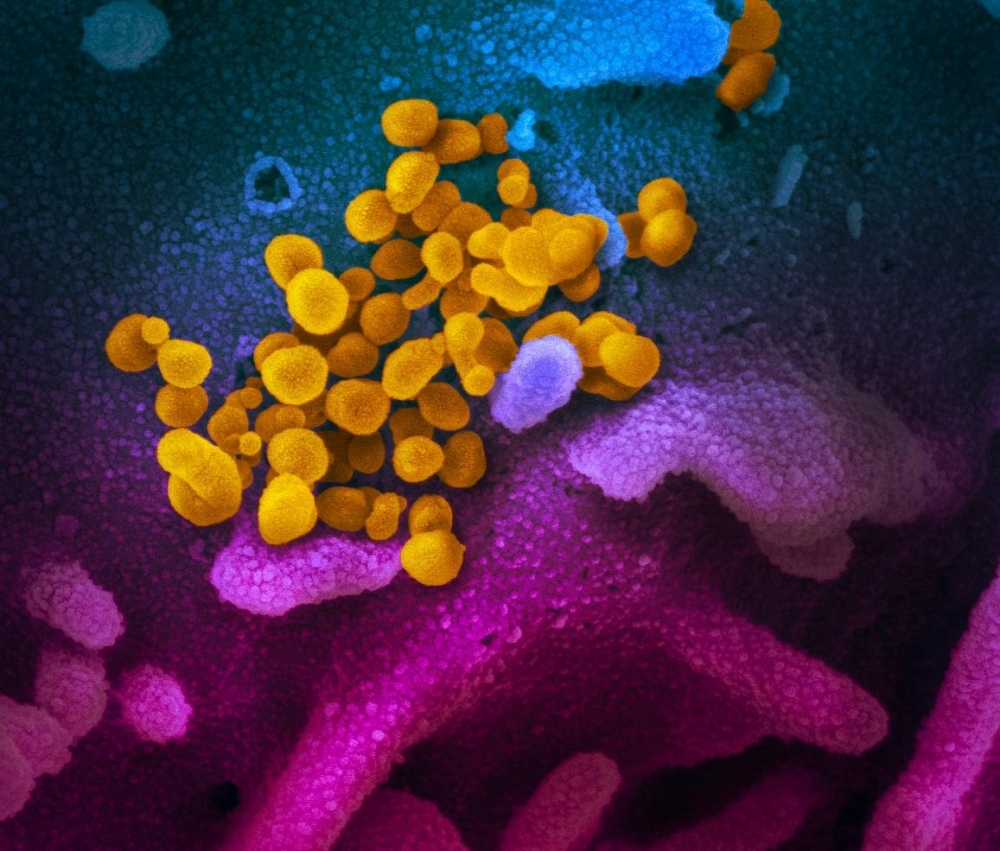

Scanning electron microscope image of SARS-CoV-2 (yellow), isolated from a patient, emerging from the surface of cells (blue/pink) cultured in the lab (image: NIAD / HIH)

Scientists in the state of São Paulo are working on a method of diagnosing the disease quickly and cheaply by combining an analysis of the pattern of molecules in body fluids with machine learning.

Scientists in the state of São Paulo are working on a method of diagnosing the disease quickly and cheaply by combining an analysis of the pattern of molecules in body fluids with machine learning.

Scanning electron microscope image of SARS-CoV-2 (yellow), isolated from a patient, emerging from the surface of cells (blue/pink) cultured in the lab (image: NIAD / HIH)

By Karina Toledo | Agência FAPESP – In Brazil, researchers at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) and the University of São Paulo (USP) have joined forces to produce a low-cost rapid test to diagnose COVID-19 while also identifying patients who risk developing respiratory failure.

The test will use a method based on an analysis of the pattern of molecules found in body fluids and is expected to cost about 8-12 dollars.

“We’ve applied for approval by CONEP [Brazil’s National Research Ethics Committee, which regulates clinical trials], and are currently doing preparatory analysis and data processing. All at the same time, given the situation,” Rodrigo Ramos Catharino, head of UNICAMP’s Innovare Biomarker Laboratory told Agência FAPESP.

Catharino’s main research interest is the search for biomarkers of disease by means of metabolomics (analysis of all the metabolites in a biological sample) combined with machine learning, a subset of artificial intelligence. More specifically, he aims to identify biomarkers that help diagnose and estimate prognosis for metabolic syndrome, viral infections and cystic fibrosis, among other conditions.

The first step in developing the test will be to analyze samples in a mass spectrometer, a kind of molecular scales that detects all the metabolites present in body fluids and produces a profile of the various metabolic processes at work in the organism.

The next step, which will be conducted at UNICAMP’s Institute of Computing and led by Professor Anderson Rezende Rocha, will consist of using machine learning tools to analyze the results of tests of samples from both individuals with COVID-19 and healthy subjects serving as controls. Here the aim is to “train” the computer program to recognize patterns representing healthy organisms, patients with the novel coronavirus disease and the most severe cases of the disease.

Sample collection

Recruitment of volunteers and collection of samples are the responsibility of a team led by Rinaldo Focaccia Siciliano, affiliated with Hospital das Clínicas (HC), the teaching hospital run by the University of São Paulo’s Medical School (FM-USP). Siciliano is an attending physician in HC’s Infectious and Parasitic Disease Division and the Hospital Acquired Infection Control Unit at its Heart Institute (INCOR).

Siciliano told Agência FAPESP that participants will be selected from among patients admitted to HC with flu-like symptoms such as fever, cough, sore throat and runny nose, and patients with the same symptoms attending the Municipal Hospital in Lapa, a neighborhood of São Paulo City.

“We want our population sample to be heterogeneous,” he said. “HC is a tertiary hospital [where specialists treat patients with severe conditions referred by providers of primary and secondary care] and the Lapa Municipal Hospital is an open-door emergency room that receives all kinds of cases.”

According to Siciliano, samples will be collected from three groups: patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 based on the molecular techniques in routine use; patients with a confirmed diagnosis of influenza; and patients with flu-like symptoms but negative test results for both pathogens.

“We estimate we’ll need 50 samples from each group plus 50 from healthy people as controls. We expect to be able to complete the collection stage shortly because of the pandemic,” he said.

The advantage of rapid tests, he added, is that they can remove patients from circulation to prevent transmission of the virus. “In addition, if we can predict the cases with the highest risk, we can offer a more appropriate level of care,” he said.

According to Catharino, once the procedures and software are ready and validated, it will be possible to perform more than 1,000 tests per day. “It will be faster than the method used now, cost less, and offer more information to help health workers and doctors make hospitalization and treatment decisions,” he said.

Ester Sabino, a professor at FM-USP and one of the designers of the study, will be responsible for having the samples stored at USP’s Tropical Medicine Institute (IMT).

José Carlos Nicolau, also a professor at FM-USP and head of INCOR’s Acute Coronary Artery Disease Clinical Unit, is charged with meeting another of the project’s goals: understanding how the novel coronavirus affects blood platelet aggregation and coagulation, as well as the clinical implications of these processes.

“In investigating what happens to platelet aggregation and other markers of coagulation, we want to compare and contrast these variables in the groups mentioned [patients with respiratory discomfort hospitalized with COVID-19, with flu, with neither, and the control group],” Nicolau said. “The results could have prognostic and therapeutic implications. If I find that a given parameter negatively influences the patient’s condition, I can try intervening to block the process in order to improve the condition.”

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.