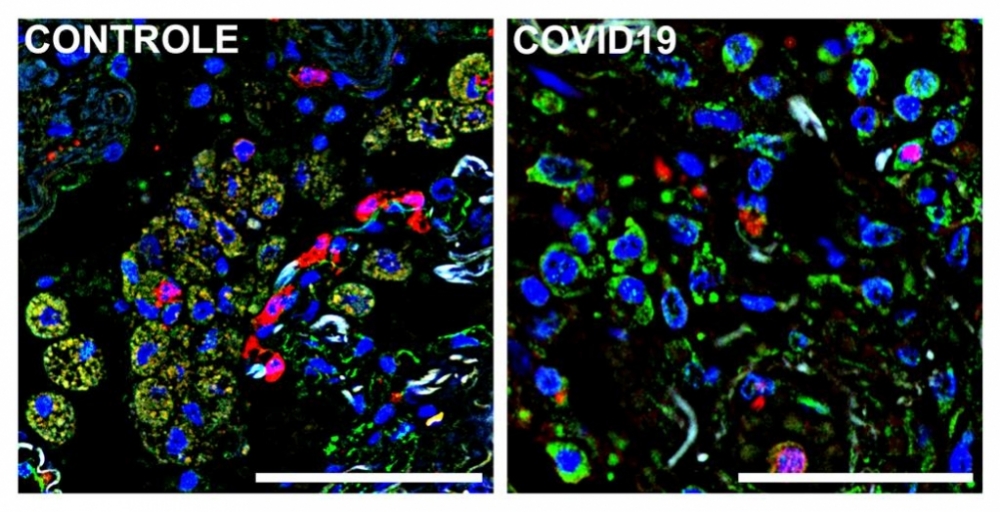

Immunofluorescence images of autopsied lung tissue from a patient who died of COVID-19 (right) and a patient who died of an unrelated cause (left). Cell nuclei are blue; a marker (S1009) of lung-infiltrating monocytes and macrophages is green; and receptor CD36 is red. Macrophages and monocytes that express both S1009 and CD36 appear beige owing to red-green superimposition (image: Alexandre Fabro & Edismauro Freitas-Filho)

A study by the University of São Paulo has discovered that when macrophages engulf cells infected by the novel coronavirus, they begin producing excessive amounts of pro-inflammatory molecules, and their capacity to recognize and phagocytize dead cells is reduced twelvefold.

A study by the University of São Paulo has discovered that when macrophages engulf cells infected by the novel coronavirus, they begin producing excessive amounts of pro-inflammatory molecules, and their capacity to recognize and phagocytize dead cells is reduced twelvefold.

Immunofluorescence images of autopsied lung tissue from a patient who died of COVID-19 (right) and a patient who died of an unrelated cause (left). Cell nuclei are blue; a marker (S1009) of lung-infiltrating monocytes and macrophages is green; and receptor CD36 is red. Macrophages and monocytes that express both S1009 and CD36 appear beige owing to red-green superimposition (image: Alexandre Fabro & Edismauro Freitas-Filho)

By Karina Toledo | Agência FAPESP – An unbalanced immune response to SARS-CoV-2 underlies progression to the severe form of COVID-19, according to a growing consensus among scientists, but it is unclear exactly which components of the body’s defense system are out of control in these cases and why. In a study reported on the preprint platform medRxiv, researchers at the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil appear to have completed a key portion of the jigsaw puzzle.

In the article, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, the researchers describe how contact with the novel coronavirus alters the functioning of macrophages, white blood cells that act as the immune system’s “trashmen” by detecting, engulfing and destroying pathogens and dead cells through phagocytosis.

Experiments conducted on cell cultures in the laboratory showed that when a macrophage digests a cell infected by a still active SARS-CoV-2, it begins producing excessive amounts of pro-inflammatory molecules, potentially contributing to the phenomenon known as a cytokine storm, seen in severe COVID-19 patients. In addition, according to the study, engulfing an infected dead cell reduces the macrophage’s capacity to recognize and phagocytize other dead cells by as much as a factor of 12.

“Millions of cells die in our organism every day. They have to be eliminated efficiently. Otherwise, they may be interpreted as a sign of danger or generate autoantigens that favor the development of an autoimmune disease. In the case of lungs affected by SARS-CoV-2, continuous removal of dead cells by macrophages is essential to tissue regeneration. If the presence of the virus in a phagocytized cell subverts this function of macrophages, it may contribute to the extensive tissue damage characteristic of COVID-19,” Larissa Cunha, last author of the article, told Agência FAPESP. A professor at the University of São Paulo’s Ribeirão Preto Medical School (FMRP-USP), Cunha was principal investigator for the project, which was funded by FAPESP.

Preliminary evidence

The first tests described in the article involved two lines of epithelial cells, one originally from a human lung (Calu-3) and another from a monkey’s kidney (Vero CCL81, one of the most widely used models in COVID-19 research). They were infected in vitro with SARS-CoV-2. The researchers found that the infection activates in epithelial cells a process known as apoptosis, a type of programmed cell death that normally does not trigger an inflammatory response in the organism.

In parallel, the researchers used ultraviolet radiation to induce apoptosis in a separate set of epithelial cells.

The apoptotic cells in both groups (infected with the virus and exposed to radiation) were collected and placed to interact with cultured macrophages derived from human monocytes (another type of white blood cell).

As expected, when the macrophages engulfed the cells killed by radiation, they assumed an anti-inflammatory phenotype favoring repair of damaged tissue, but when they engulfed cells containing SARS-CoV-2 viable enough to infect other cells, this programming was lost and the macrophages began secreting large amounts of pro-inflammatory molecules such as interleukin 6 (IL-6) and interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β).

“Collectively, our findings provide evidence that engulfment of dying cells carrying viable SARS-CoV-2 switches the anti-inflammatory resolutive programming in response to efferocytosis toward an inflammatory phenotype. The exacerbated cytokine production observed in response to the efferocytosis of infected corpses by macrophages may contribute to the hyper inflammation associated with COVID-19,” the article concludes. Efferocytosis is the process by which apoptotic cells are removed by phagocytic cells.

Impaired efficiency

In the next stage, the researchers investigated what happened to gene expression by macrophages after they engulfed apoptotic cells infected by SARS-CoV-2. They detected a fall in the expression of key genes for macrophage activity, including TIM4, SRA-I, CD36 and ITGB5.

“These genes encode receptors [proteins] located on the macrophage’s membrane and recognize a substance called phosphatidylserine, considered a universal marker of cell death,” Cunha said.

This phospholipid is usually located inside the cell membrane, she explained, but when the cell dies it is exposed on the outer surface, where it can be recognized by macrophages via receptors such as TIM4 and CD36.

“To repair damage efficiently and prevent an accumulation of necrotic material in the organism, macrophages must be able to recognize and constantly clear away dead cells, one after another. However, our experiments show that when they engulf cells containing SARS-CoV-2, this phagocytic capacity is significantly reduced,” Cunha said.

When epithelial cells killed by radiation were placed in macrophage cultures, their capacity to carry out this cleansing function was reduced twelvefold if they had previously been in contact with cells infected by the virus.

In another test, cultured human macrophages were infected directly with SARS-CoV-2. Phagocytic activity decreased, but only by a factor of 2.

Patients’ cells

Analysis of blood samples from patients with moderate or severe COVID-19, collected on admission to hospital, showed high levels of pro-inflammatory molecules such as IL-6, IL-1β, interleukin 8 (IL-8), and interleukin 10 (IL-10). They also had higher levels of circulating monocytes (white blood cells that give rise to macrophages) than healthy subjects, and a larger proportion of monocytes with a pro-inflammatory phenotype.

The analysis of gene expression showed lower monocyte expression of the receptors CD36, SRA-I, ITGB5 and TIM4 in COVID-19 patients compared to those of healthy subjects. The more severe the symptoms reported on admission, the sharper the fall in expression of phagocytic receptors.

In the next test, the monocytes from COVID-19 patients were challenged in vitro with apoptotic cells from mice. As expected, they performed their cleansing function much less efficiently than monocytes isolated from the blood donated by healthy volunteers.

With the aid of bioinformatics, in collaboration with Helder Nakaya, a professor at USP’s School of Pharmaceutical Sciences (FCF), the researchers reanalyzed gene expression data from previously published studies available from public databases. The analysis confirmed that the expression of genes that promote phagocytosis of dead cells was much more sharply reduced in severe COVID-19 patients than in patients with mild symptoms.

Lastly, the researchers analyzed lung-infiltrating defense cells in autopsy samples from people who died of COVID-19. “We focused on mononuclear cells that had been recruited from the bloodstream to combat the virus in the lungs,” Cunha said. “Here, too, we observed reduced expression of the receptors, which suggests the phagocytic capacity of these defense cells was compromised.”

According to the authors, impaired efferocytosis may contribute to the accumulation of dead cells and extensive tissue damage observed in the lungs of COVID-19 patients. “This may explain the respiratory complications developed by patients with the severe form of the disease and their increased susceptibility to secondary bacterial infections,” they write in the article.

Other collaborators in the study included the Center for Research on Inflammatory Diseases (CRID), a Research, Innovation and Dissemination Center (RIDC) funded by FAPESP, and physicians and researchers at Hospital das Clínicas, the general and teaching hospital run by FMRP-USP. The co-authors of the article include Fernando Q. Cunha, Alexandre T. Fabro, Helder Nakaya, Dario S. Zamboni, Paulo Louzada-Junior, and Rene D. R. Oliveira, all of whom are professors at FMRP-USP.

The article “Efferocytosis of SARS-CoV-2-infected dying cells impairs macrophage anti-inflammatory programming and continual clearance of apoptotic cells” is at: www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.18.21251504v1.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.