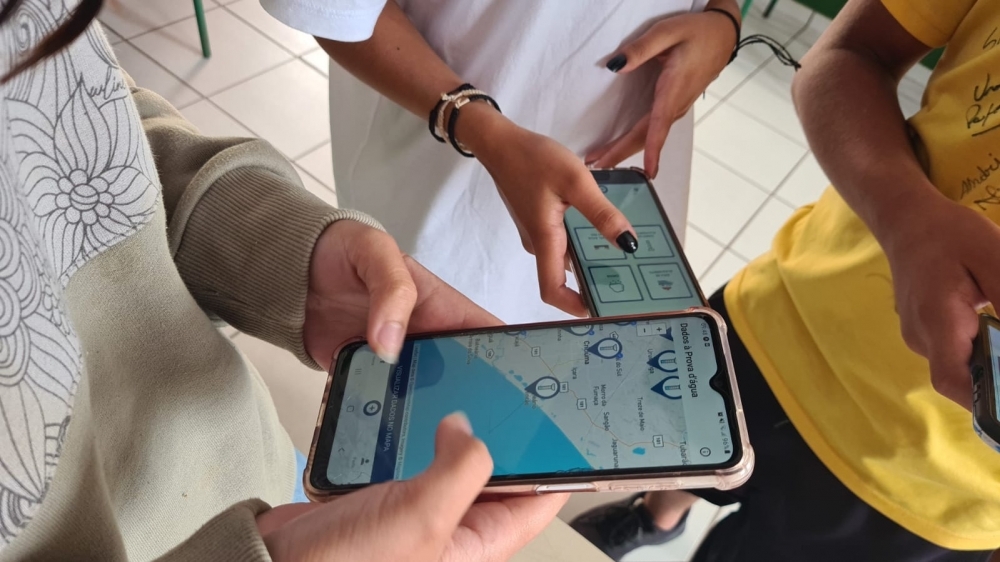

Students in Balneário Rincão (Santa Catarina, Brazil) using the Waterproofing Data app. Community involvement in its development helped map flood-prone areas (photo: Rosinei da Silveira)

The app is one of the outcomes of an initiative by researchers in Brazil, Germany and the UK to engage local communities in generating data on flood-prone areas. The researchers are also collecting memories of past incidents.

The app is one of the outcomes of an initiative by researchers in Brazil, Germany and the UK to engage local communities in generating data on flood-prone areas. The researchers are also collecting memories of past incidents.

Students in Balneário Rincão (Santa Catarina, Brazil) using the Waterproofing Data app. Community involvement in its development helped map flood-prone areas (photo: Rosinei da Silveira)

By André Julião | Agência FAPESP – A smartphone app could change the way communities and governments deal with floods. People living in flood-prone areas can use it to receive early warnings and help the authorities with disaster prevention by contributing to the identification of high-risk areas.

The app is one of the outcomes of Waterproofing Data, a project involving researchers from the Universities of Glasgow (Scotland), Warwick (England) and Heidelberg (Germany); the National Disaster Surveillance and Early Warning Center (CEMADEN) and Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV) in Brazil, with FAPESP’s support; and the United Kingdom Research and Innovation Global Challenges Research Fund.

“The basic principle is that technology, engaging people and data generation, use and circulation improve the resilience of communities that are vulnerable to socio-environmental disasters – in this case, floods,” said Maria Alexandra da Cunha, principal investigator for the Brazilian part of the project. Cunha is a professor at FGV’s Business School (EAESP).

A survey conducted in 2020 by the National Confederation of Municipalities (CNM) found that 1,697 decrees had been issued by local authorities that year in Brazil to declare a state of emergency or public calamity because of heavy rain.

According to CNM’s civil defense division, the damage done by storms, cyclones, landslides, floods and tornadoes reached BRL 10.1 billion. Housing was worst affected: 280,486 homes were damaged or destroyed, accounting for losses worth BRL 8.5 billion.

The app has been tested by teachers, students, civil defense personnel and residents in more than 20 cities in the states of Pernambuco, Santa Catarina, Mato Grosso, Acre and São Paulo. It is called Dados à Prova D’Água, the Portuguese-language equivalent of Waterproofing Data, and can be downloaded from Google Play, the official store for Android apps.

The researchers use citizen science to collect data for the system, training state school students to set up homemade rain gauges using PET bottles and simple rulers. Each student is responsible for recording the rainfall measured by a rain gauge every day and entering the data into the app, which sends it to the system’s database. The idea is for this data to contribute to future disaster prevention plans.

“The data required for disaster hazard management traditionally flows in one direction only, from centers of expertise to the population and local authorities. The app is designed to introduce a flow in the other direction as well, promoting direct community participation and supplying local data to specialized centers,” said Mário Martins, a researcher on the project and a postdoctoral fellow of EAESP-FGV with a scholarship from FAPESP.

Users of the app can enter data on flooded areas, heavy rain and river water depth. The system also stores data supplied by CEMADEN and CPRM, the national geological service, for use by local communities.

“We didn’t set out just to develop an app. During our activities in the study areas, we took pains to discuss how the app could be used by residents during a disaster. As a result, we actually developed a new method of software development and a tool that can be used by anyone,” said Lívia Degrossi, also a postdoctoral researcher at EAESP-FGV.

Degrossi developed the app in collaboration with members of CEMADEN and Acre state’s environmental department and civil defense. Students at two secondary schools (“Renato Braga” and “Vicente Leporace”) in Jardim São Luís, part of M’Boi Mirim, a district of São Paulo City, and residents of the neighborhood participated in the project. According to the São Paulo-based Technological Research Institute (IPT), M’Boi Mirim has more high-risk areas than any other in the city.

Flood memories

“We work with state schools in poor areas with a history of flooding. Jardim São Luís has many streams and hills, so it’s vulnerable to flooding and landslides. We set out to create data and promote the circulation of existing data held by government agencies but not accessible to local communities,” said Fernanda Lima e Silva, also a postdoctoral researcher at EAESP-FGV with a scholarship from FAPESP.

Lima e Silva worked with Degrossi on the production of a handbook for secondary school teachers on how to develop a course in disaster prevention, citizen science and the impact of climate change on people’s everyday lives. The teachers at the schools involved in the project collaborated, as did CEMADEN Education, which will post the handbook to its website.

Besides disaster prevention, the project is also collecting flood memories. The secondary school students from Jardim São Luís interviewed elderly relatives and told their classmates about the stories they heard, highlighting the information acquired regarding past floods in the locality. They also interviewed other older members of the community for a series of short documentaries called Waterproofing Memories (Memórias à Prova D´Água), one of which can be watched online.

The project also involves researchers at Warwick University who are collecting memories of disasters and working on ways to foster community resilience.

A chapter has been written for a book and will be included in a special issue of Bulletin of Hispanic Studies on memory and sustainability to be published in 2023.

“Part of our research also focuses on perceptions of risk, where members of the local community pinpointed disaster-prone areas on the map,” Lima e Silva said. “This kind of knowledge is far more detailed than the databases of local authorities. You can drill down to street corner level. The mapping exercise detected a major problem with storm runoff, for example.”

The researchers held collaborative mapping workshops on OpenStreetMap, which is free and lets users add data to maps via an open-content license. They did this to map the area and draw attention to the risk of floods and landslides.

This year the group will issue a manual to help communities in other parts of Brazil implement the program. “It’s very important for people to engage with the data, from generation to use. We hope to be able to help spread this practice and enhance resilience in these communities, as extreme weather events are becoming increasingly frequent,” Cunha said.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.