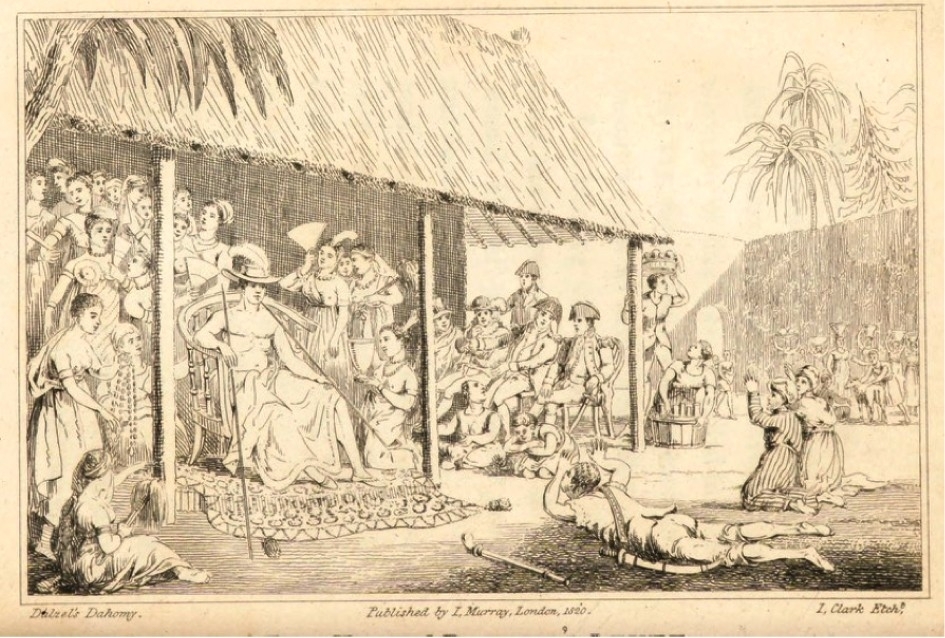

An illustration from a travel book by John M’Leod, a British naval surgeon on a slave ship that docked at Ouidah in 1803. The King (Dada) of Dahomey on a dais at a public viewing (source: A voyage to Africa with some account of the manners and customs of the Dahomian people, by John M’Leod, London, John Murray, 1820)

Research by a student at the University of São Paulo examines embassies sent to Brazil by the African kingdom in the period 1795-1805. Their purpose was to build closer ties with the Portuguese authorities and Brazilian slave buyers.

Research by a student at the University of São Paulo examines embassies sent to Brazil by the African kingdom in the period 1795-1805. Their purpose was to build closer ties with the Portuguese authorities and Brazilian slave buyers.

An illustration from a travel book by John M’Leod, a British naval surgeon on a slave ship that docked at Ouidah in 1803. The King (Dada) of Dahomey on a dais at a public viewing (source: A voyage to Africa with some account of the manners and customs of the Dahomian people, by John M’Leod, London, John Murray, 1820)

By José Tadeu Arantes | Agência FAPESP – Brazil was the country that received the most enslaved Africans and the last in the West to abolish slavery formally. According to reliable estimates, 4.8 million Africans were transported to Brazil and sold as slaves, while 670,000 died on the journey. This key element in the formation of Brazilian society remains an open wound 133 years after formal abolition.

For over three centuries, three groups of protagonists combined their interests to establish and maintain this abominable trade: large buyers who lived in Brazil and were especially active in the ports of Salvador and Rio de Janeiro; Atlantic traders, many of them European, responsible for more than 9,000 shipments of slaves from the coast of Africa to Brazil; and the rulers of African societies, who warred among themselves with the aim of capturing, enslaving and selling their adversaries.

These rulers used merchandise such as textiles, rum and other spirits, tobacco, furniture and animals bought with the proceeds of slaving to curry favor with their supporters and keep themselves in power. Above all, they were interested in firearms for use in warfare and to capture more slaves. “It was a vicious circle: selling slaves got them guns, and guns enabled them to seize more slaves. The slave trade fueled rivalry, stimulated wars, and profoundly disorganized traditional African societies,” says historian Marina de Mello e Souza, a professor in the Department of History at the University of São Paulo’s School of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences (FFLCH-USP) in Brazil.

Her student Raphael dos Santos Gonçalves investigated a less well-known aspect of this politico-commercial undertaking: the two “embassies” sent to Brazil in the period 1795-1805 by the kingdom of Dahomey (located in West Africa between 1600 and 1904 within present-day Benin), with the aim of building closer ties with the Portuguese colonial authorities and slave buyers residing in Brazil, and making sure they continued to buy slaves supplied by Dahomey rather than rival kingdoms. His study, “Os ‘embaixadores’ do comércio de escravos na América Portuguesa: diplomacia entre tensões e tradições (1795-1805)”, was funded by a scientific initiation scholarship from FAPESP and recently won an honorable mention at the University of São Paulo’s 28th International Symposium on Scientific and Technological Initiation (SIICUSP).

“The city of Salvador in Bahia traded continuously with the various African kingdoms in the Gulf of Benin region,” Santos Gonçalves says. “There were several African slave ports, each controlled by a different warlord or king. According to historian Robin Law, Ouidah, ruled by Dahomey from 1727, was the most active slave port in Africa. More than 50% of the people enslaved in the Gulf of Benin region were deported from Ouidah.”

The relations between Ouidah and Salvador, and their mutual influences, were studied by researchers such as Pierre Verger and Mariza de Carvalho Soares. In the prizewinning novel Um defeito de cor by Ana Maria Gonçalves, strongly grounded in historical fact, these relations are the backdrop for a story about an old African woman in search of her enslaved son in Brazil, but Santos Gonçalves’s scientific initiation research advanced beyond secondary sources to analyze letters signed by two kings of Dahomey and transcribed by historian Luis Nicolau Parés, a professor at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA) in Salvador.

“The research showed that before sending ‘embassies’ over the Atlantic, the political elite of Dahomey already had diplomatic experience, with a sizable physical structure to host foreigners and administrative functionaries in place for this kind of dialogue,” Santos Gonçalves says. “The courtesies included even banquets served in the European manner at Abomey, the capital of the kingdom. The Luso-Brazilian authorities welcomed the emissaries from Dahomey in the name of maintaining ‘good harmony’ with the exporters of slaves, but rejected all proposals for a monopoly on the slave trade.”

Inspired by the historiography of Law and Kristin Mann, Santos Gonçalves also showed the importance to this diplomacy of go-betweens in the “Atlantic community” consisting of Portuguese, British, French, Luso-Brazilians, and above all “Euro-Africans”, offspring of Europeans and Africans. Ambitious, audacious and capable, the members of this “community” were at home in both cultures and involved in the slave trade in one way or another. They included the scribes and translators responsible for writing the letters signed by the kings of Dahomey.

Two important events happened during the period covered by the study: the arrival in Dahomey of Vicente Ferreira Pires, a Luso-Brazilian priest sent there in 1796 to convert the king to Catholicism, and the enthronement of Adandozan as the successor to King Agonglo in 1797.

“Agonglo supported the Catholic priest’s mission and said he wanted to convert, but while preparations were being made for his baptism, he was assassinated by political adversaries who put his son Adandozan on the throne,” says Santos Gonçalves.

As part of this palace coup, Queen Na Agontimé, one of Agonglo’s wives, was enslaved and sold by Adandozan to the traders. Although Santos Gonçalves does not discuss the episode, it is worth noting here because of the cultural and religious importance it came to have in Brazil. According to Verger, Na Agontimé was sent as a slave to São Luís do Maranhão, where she was baptized and christened Maria Jesuína. She did not convert to Catholicism, however. She was eventually freed and founded the famous Casa das Minas, the most important temple dedicated to Vodun worship in Brazil.

“The slave trade, which became a highly profitable business, stimulated these dissensions both between different African societies and within the ruling clans,” notes Mello e Souza. “The African chieftains bartered with their enemies, both external and internal. For example, there were major conflicts among the big men of Dahomey, whose slave port was Ouidah, and those of Oyo, who used the port of Lagos.”

Except in Luanda in the first half of the seventeenth century, when the Portuguese conquest was followed by the enslavement of local inhabitants, she adds, Europeans did not themselves take slaves but purchased people who were already enslaved. “Enslavement required wars and deep incursions into the continent,” she explains. “The Europeans concentrated on coastal areas and there set up shop to buy slaves supplied by mechanisms internal to African societies. It was only in the mid-nineteenth century that Europeans reached the heart of the continent, embarking on the process of colonization.”

An article in which Santos Gonçalves expounds on some aspects of his research (in Portuguese) is at: www.revistas.usp.br/humanidades/article/view/159331/170444/.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.